Automatically replacing text in dynamic webpages (or: have web standards become too bloated?)

Introduction and Motivation

Find and replace.

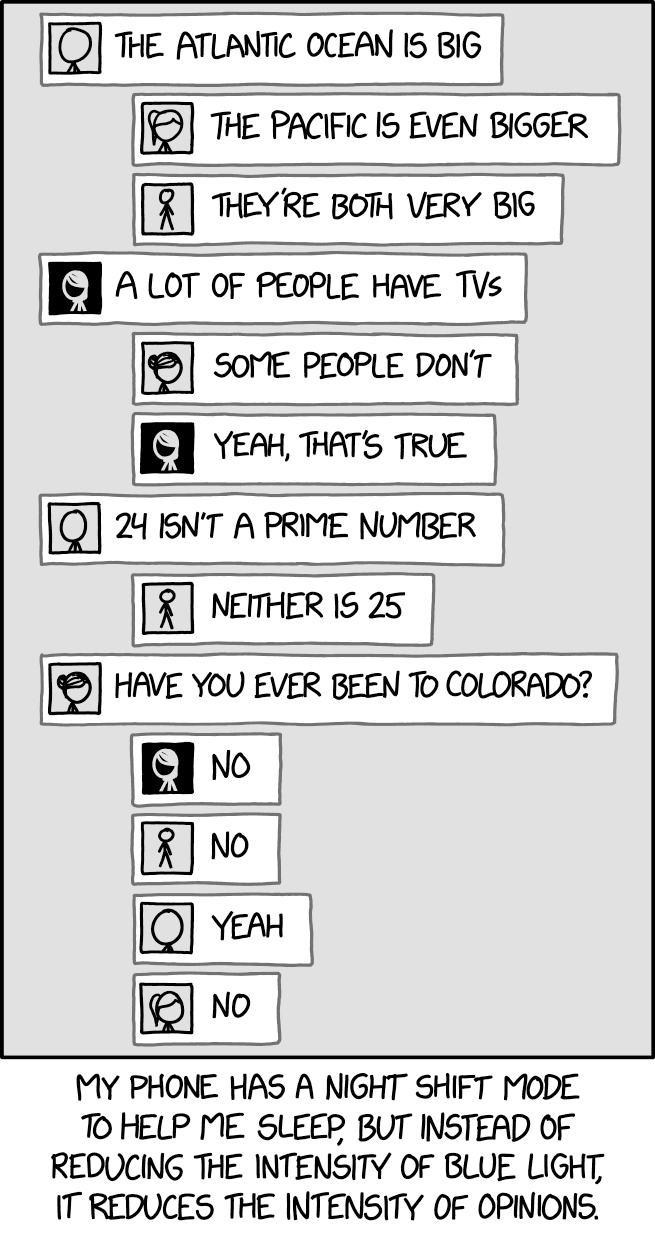

This operation is something every programmer is familiar with. It is ubiquitous in a huge variety of apps due to its incredible versatility yet simple implementation. At least, you would think it would be simple. In many programs, it probably is. But in the domain of websites, it is anything but. My inspiration for this library came from XKCD 2112: Night Shift.

My idea was to create a browser extension that does some primitive version of that by, say, substituting strong words with softer ones (“extremely” to “a little”) and cutting out swear words entirely. To do this, I would need a reliable and performant way to manipulate the text on a webpage. Not only that, I would need to monitor the DOM and process any text added or modified after initial load, because almost every site nowadays has the ability to dynamically request new content with background AJAX calls (think about when you press “more comments” on Reddit or switch channels in Discord: these actions don’t need to refresh the entire page). This turned out to be quite a nontrivial problem and TextObserver was born out of the resulting rabbit hole.

Explanation

There are two main functional pieces of a TextObserver object: the part that finds and replaces text already on a page and the part that watches for added or changed text. I will discuss the former first because it makes up the meat of the library and is used by the latter. To understand how to programatically edit the text on a site, we need to know that text can be found in the DOM as multiple representations, of which all but one can be seen as special cases. We will go over how to process each one by one.

Textnodes. These are what the text in between HTML element tags show up as.- Special attributes like

<input>placeholders (andvaluefor those oftype="button",<img>alttext, andtitle(tooltips). These are notTextnodes but are rendered as front-facing text by the browser. - The CSS

contentproperty. This is even trickier to deal with since it’s effectively invisible to the DOM but still seen by the end user.

Text nodes

The “default” representation and by far the most straightforward to replace. We use a TreeWalker to go through every Text node and replace their contents. In all of the following snippets, assume callback is a function that accepts a string as a parameter and returns the string to replace it with.

const callback = text => text.replaceAll(/heck/gi, 'h*ck');

const nodes = document.createTreeWalker(document.body, NodeFilter.SHOW_TEXT, {

acceptNode: node => valid(node) ? NodeFilter.FILTER_ACCEPT : NodeFilter.FILTER_REJECT

});

while (nodes.nextNode()) {

nodes.currentNode.nodeValue = callback(nodes.currentNode.nodeValue);

}

Wait, where did the valid() function come from? Well, it turns out there are some exceptions…

- The observation code runs asynchronously, so a node might be removed from the document before we get a chance to process it.

- Inline text between

<script>and<style>tags are actuallyTextnodes too. Messing with them could break the functionality and presentation of the page, respectively. - We don’t want to touch

contentEditableelements because doing so messes with the cursor position, making for a definitely horrible user experience. - Some text may be in an icon font. Icon fonts are special fonts that render specific character sequences as icons. For example, “search” might display as a magnifying glass. Modifying the text would prevent the icon from showing properly.

To check for this, we create valid():

function valid(node) {

return (

// Sometimes the node is removed from the document before we can process it

node.parentNode !== null

// HTML tags that permit textual content but are not front-facing text

&& node.parentNode.tagName !== 'SCRIPT' && node.parentNode.tagName !== 'STYLE'

// Ignore contentEditable elements as touching them messes up the cursor position

&& !node.parentNode.isContentEditable

// HACK: workaround to avoid breaking icon fonts

&& !window.getComputedStyle(node.parentNode)

.getPropertyValue('font-family').toUpperCase().includes('ICON')

);

}

Special attributes

The above is sufficiently thorough for, if I had to guess, 97% of cases. For most people, that should be enough. But if the last three percent is important, we must take into account some special cases, the first of which are certain attributes that the browser displays as user-visible text:

placeholderin<input>and<textarea>altin<img>,<area>, and<input type="image">valuein<input type="button">title

We can put the above data into a dictionary with attributes as keys and selectors as keys. From there, replacing the attributes is not too hard:

const WATCHED_ATTRIBUTES = {

'placeholder': ['input', 'textarea'],

'alt': ['img', 'area', 'input[type="image"]', '[role="img"]'],

'value': ['input[type="button"]'],

'title': ['*'],

}

for (const [attribute, selectors] of Object.entries(WATCHED_ATTRIBUTES)) {

document.body.querySelectorAll(selectors.join(', ')).forEach(element => {

const value = element.getAttribute(attribute);

if (value !== null) {

element.setAttribute(attribute, callback(value));

}

});

}

CSS content

The CSS content property can be used to generate text, usually used with the ::before or ::after pseudo-elements (but also available on ::marker). CSS-generated content is not visible in the DOM, so we must use a roundabout hack: call getComputedStyle to read off every pseudo-element’s content. If the property value is a plain string (content can accept many value types, including images and counters), then inject our own style rule which overrides the property for that specific pseudo-element.

const styleElement = document.createElement('style');

document.head.appendChild(styleElement);

let styles = '';

let i = 0;

const elements = document.createTreeWalker(document.body, NodeFilter.SHOW_ELEMENT);

while (elements.nextNode()) {

const node = elements.currentNode;

for (const pseudoClass of ['::before', '::after', '::marker']) {

const content = window.getComputedStyle(node, pseudoClass).content;

// Only process values that are plain single or double quote strings

if (/^'[^']+'$/.test(content) || /^"[^"]+"$/.test(content)) {

const newClass = 'TextObserverHelperAssigned' + i;

node.classList.add(newClass);

// Substring is needed to cut off open and close quote

const result = callback(content.substring(1, content.length - 1));

styles += `.${newClass}${pseudoClass} {

content: "${result}" !important;

}`;

}

}

i++;

}

styleElement.textContent = styles;

Observer

Now that we have a way to robustly substitute text across a document, we can start working on the part that does the observation. The MutationObserver interface provides a way to track updates in the DOM. We can extract all of our previous code to a processNodes() function and replace every instance of document.body with a single parameter representing the root node and leverage that in our observation callback.

const IGNORED = [

Node.CDATA_SECTION_NODE,

Node.PROCESSING_INSTRUCTION_NODE,

Node.COMMENT_NODE,

];

const CONFIG = {

subtree: true,

childList: true,

characterData: true,

characterDataOldValue: true,

attributeFilter: Object.keys(WATCHED_ATTRIBUTES),

};

const observer = new MutationObserver((mutations, observer) => {

// Disconnect every observer after collecting their records

// Otherwise, the callback's mutations will trigger an infinite feedback loop

observer.disconnect();

for (const mutation of mutations) {

const target = mutation.target;

const oldValue = mutation.oldValue;

switch (mutation.type) {

case 'childList':

for (const node of mutation.addedNodes) {

if (node.nodeType === Node.TEXT_NODE) {

if (valid(node)) {

node.nodeValue = callback(node.nodeValue);

}

} else if (!IGNORED.includes(node.nodeType)) {

// If added node is not text, process subtree

processNodes(node);

}

}

break;

case 'characterData':

if (!IGNORED.includes(target.nodeType) && valid(target)) {

target.nodeValue = callback(target.nodeValue);

}

break;

case 'attributes':

const attribute = mutation.attributeName;

const value = target.getAttribute(attribute);

if (value !== undefined && value !== null) {

// Find if element with changed attribute matches a valid selector

const selectors = WATCHED_ATTRIBUTES[attribute];

let matched = false;

for (const selector of selectors) {

if (target.matches(selector)) {

matched = true;

break;

}

}

if (matched) {

target.setAttribute(attribute, callback(value));

}

}

break;

}

}

observer.observe(document.body, CONFIG);

});

// Perform initial replacement

processNodes(document.body);

// Set up observer

observer.observe(document.body, CONFIG);

The length may be intimidating but this part is relatively straightforward compared to what we’ve gone through. We check each mutation and if it’s an added node, we process it recursively leveraging the processNodes() function we wrote previously. If it’s a changed CharacterData node we have to check that it is a real Text node and not one of the other types that implement the more general CharacterData interface. And if it’s an attribute we check if the changed element is one we’re actually watching. Believe it or not, we are now done! Hopefully this was helpful in documenting the thought process and structure behind TextObserver.

Just kidding, the web is complicated

This code doesn’t work on <iframe>s. It misses Shadow DOMs. It chokes on “recursive” replacements (e.g. try replacing ‘e’ with ‘ee’ and you’ll occasionally end up with ‘eeee’). And online word processors might show quirky behavior. This isn’t all of the code in TextObserver. The full library provides extra convenience functions as well as mitigations for some of the above, but at well over 300 lines, explaining every single line would turn this post into a book.

As what I thought would be a simple function grew into several hundred lines, I started to wonder if web standards are becoming too complex. Sure, you could ignore all the edge and corner cases and get 95% of the way there with a fraction of the code, but philosophically speaking, I can’t help but feel like this should be a one-liner for what is supposed to be a declarative markup language. And of course HTML/CSS/JavaScript are far more powerful than what we typically think of a markup language like the Markdown that this post is written in, and users and developers are constantly demanding new features.

I get the sentiment; despite enjoying the typical jabs at web development, I have begrudgingly concluded that the open web could be the easiest way to create true cross-platform apps that aren’t locked in to a specific ecosystem and can reach everyone, be it a Silicon Valley CEO’s workstation computer or a young student hacker’s flip phone and Raspberry Pi. On the other hand, I worry that this mission creep will further reduce diversity and competition in the browser market and funnel more power to the few remaining corporate entities with enough capital to keep up. Already Drew DeVault has claimed that it is impossible to build a new browser without the funding and manpower of an immense cooperative project on the national level. This is a dilemma that I do not claim to have answers for.